Translating a book for an academic project allows for a bit of luxuriating in the text. If you’re trying to make a living out of literary translation (emphasis on the “trying” there!), then chances are you haven’t got time to sit down and read the book several times before you start. In which case, you might do a quick skim to get a taste for the narrative voice etc, or you might go straight into your first draft and read as you go – I have a feeling that’s what Daniel Hahn said he does, in Catching Fire, but I’ve lent the book to someone so don’t quote me on that because I can’t verify.

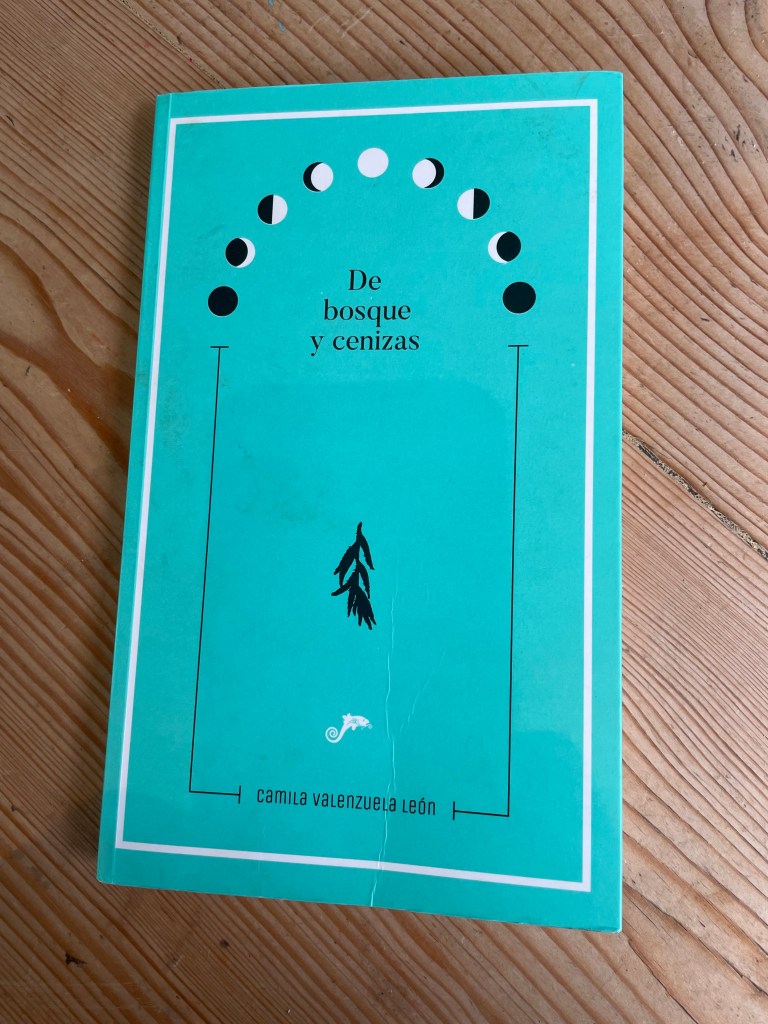

Anyway, in this particular instance I’ve got three years, possibly even four, to translate a relatively short book – it comes in at 141 pages total and is written in diary form (and a bit of verse-prose) so many of those aren’t even full pages. I’ve also only got a paperback of the original to work from, and although I have a good relationship with the author and could doubtless ask her to send me a PDF version, I decided to copy the text out into a Word document. I realise that sounds like a monumental waste of time, but actually, if you’ve got that time, I find it offers a really good opportunity for a close reading of the source text, and I noticed several things I hadn’t picked up on my initial reading, such as:

- The word “desaparecidos” is used to describe the people whose bodies have never been found (the story is set in the aftermath of the Chillán earthquake in Chile, in 1939). Obviously this is a perfectly reasonable word choice that I didn’t even think about first time round, but I’ve also just noticed that they’ve used the town stadium to house all the people whose homes were destroyed in the earthquake, and those two things combined are making me wonder if there’s some veiled reference to the Pinochet dictatorship happening… it could of course just be a coincidence, but worth checking with Camila.

- Trees! Specifically the willow, or “sauce” – this was a key feature in Las Durmientes, which I translated for my MA project, and actually – now I think about it – there’s a willow that plays a major role in the Zahorí saga (Camila’s earlier novels), too… does the willow hold some particular place in Chilean folklore, or is it something personal to Camila? Another one to check.

- Black thread (hilo negro) – this is another one that crops up in all her books, and actually I’ve noticed it (or “hilo” at least, I might want to check whether colour is referenced) in the work of other Chilean women writers too… does that warrant further investigation? I have a feeling that in Camila’s work, at least, it has something to do with the embroidery that women in Chile traditionally did and its links to storytelling – both stories told within the embroidery itself and orally, to children by the fire while the mother/grandmother embroiders

- Barely any characters have a name… this was the case in Las Durmientes, too, but doesn’t apply to Zahorí, so I suspect it is because this is a fairy tale, and characters in traditional stories are often nameless. But was it also a deliberate decision related to the objectification of women, and girls, and particularly indigenous/mestiza women? Another one to check with Camila…

And that’s all just from the first few pages. The funny thing is, when I read it through the first time, I was a bit worried there wasn’t as much to unpack as there had been in Las Durmientes, and this time I’m trying to get a whole doctoral thesis out of it. Now, of course, I’m worried there’s too much and I won’t have room to do it all justice and fit in the reflections on the workshops I plan to do once I’ve got my translation to a half-decent standard. Still, better to have too much to write than too little!

More on this next time…