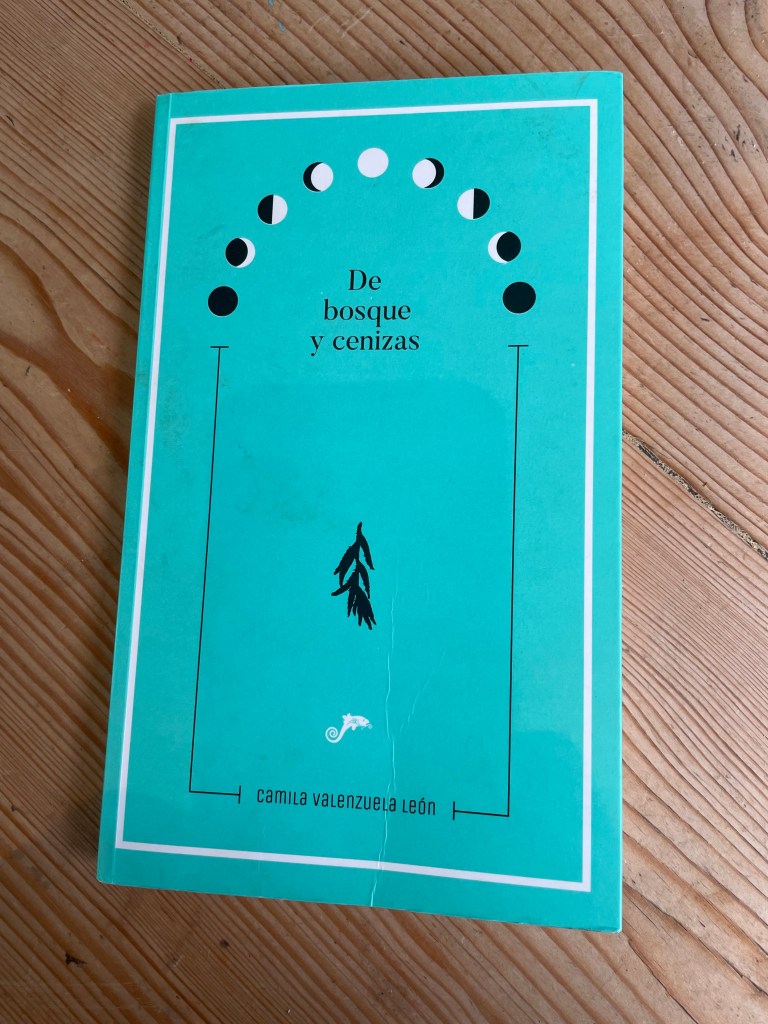

Well, after a very slow January (see previous post), this week I finally rediscovered my mojo and managed to finish off my first draft translation of De bosque y cenizas, the book I’ll be translating for my thesis.

That probably sounds quite a lot more impressive than it actually is, because the first draft is really just a gist translation, to get the text into some sort of passable English and establish where the problems are going to lie – I don’t make much of an attempt to resolve those problems at this stage, just make a note of what and where they are. There is a lot of highlighting, caps, bold type and slashes at this stage, so it’s not exactly print worthy.

But the great news is it’s got me THINKING about those thorny issues… being a literary translator often feels like being in a perennial state of having a word on the tip of your tongue, and the longer you can give yourself to find that word, the better. It almost never comes to you when you’re actually translating, it’ll be when you’re on the bus, or picking the kids up from school, or queuing at the supermarket checkout, and you have to physically stop yourself from shouting it out loud and elliciting uncomfortable looks from the people around you. And then there are the times when you’ve finished the translation, sent it off, complete with the word you weren’t quite sure about but decided would have to do, and THEN it comes to you.

As I may have mentioned before, I am in the particularly privileged position, with this translation, of having four years to get it right (there is the small matter of the actual thesis, of course). And that means I’m able to give considerably more attention to each word than I might if I had to get it to the publisher in three months’ time. I’m also devoting the first part of my literature review to Camila Valenzuela (the author)’s work, which means I’ve been reading everything she’s ever written, alongside doing this first draft. And I can tell you, if you ever find yourself with a spare four years to devote to translating one book, reading the author’s entire back catalogue makes quite the difference!

For example, I started by reading Valenzuela’s own doctoral thesis, which happened to be on gender representation in fairy tales. De bosque y cenizas is a feminist retelling of Cinderella, so I think you can see how her academic work might have been an influence, and reading her thesis gave me an insight into what she was trying to do – or avoid doing – in her literary writing, and why. More recently, as I was working on the first draft, I was also reading Valenzuela’s earliest novels – the Zahorí saga, which is an epic fantasy trilogy, set in both Ancient Ireland and modern-day Chile. The story focuses on the Azancott sisters, who have to move from Santiago to their grandmother’s house in the south of Chile, after their parents are brutally murdered. When they get there, strange things start to happen, and they gradually discover that they come from a long line of “elementals”, originally descended from druids in Ancient Ireland.

So far, so nothing-remotely-like Cinderella, you might think. But, in Valenzuela’s version of Cinderella, Prince Charming is replaced by the witches of the woods, who meet with the changing of the moon to perform ancient rituals. And because I happened to be alternating reading Zahorí with translating De bosque y cenizas I was able to recognise that a) a lot of the rites performed by the witches were based on druid tradition and b) Valenzuela clearly both revisited some of her research from the former when writing the latter, and is heavily influenced by these ancient European traditions, as well as those of the Mapuche and other Indigenous peoples of Chile. And I don’t know exactly how that knowledge is going to help me with my translation, but I am confident it will.

So there you have it, another deep dive into what’s been going on inside my head this week. More fascinating (!) insights soon…